You’re brought onto a project, and it’s a mess. The org is a tangle of undocumented automations, convoluted sharing rules, and custom objects that seem to duplicate a standard object for no apparent reason. You look at a complex flow or a legacy Apex trigger and find yourself asking: “Why? Why did they build it this way? What problem was this even trying to solve?” The original architects and developers have long since moved on, and with them, the institutional knowledge of these critical decisions has gone.

Sound familiar? As an architect, this is how I have felt on more than one occasion.

In a perfect world, every important architectural choice would be discussed in a formal document, one that any team member can look at to better understand key decisions that led to a solution. However, rigorously documenting every key decision manually is time-consuming.

This article explores how AI can be used to augment an architect’s decision-making role on projects. In my experience, only humans can provide the nuanced, project-specific context and stakeholder empathy required to establish the assessment criteria for a decision — but AI is really good at research and formatting information quickly. So, I have been exploring how to meld the best of both worlds to help kickstart decisions without starting from a blank piece of paper.

During my career, I have used many decision documentation templates, but have found one to be the most useful and easiest to adopt across project size and industry: the architectural decision record (ADR).

What is an architectural decision record (ADR)

The core purpose of an ADR is to document the “why” behind a choice. This includes the business context, alternatives considered, the trade-offs evaluated, and the final decision.

The idea is that all stakeholders, from enterprise architects to developers, are aligned on the path forward. This document is not just for future reference; it gains alignment and buy-in from stakeholders during a project as it provides a transparent record of the business rationale and any concessions that were accepted.

It’s your get-out-of-jail-free card when someone inevitably asks six months later, “Why did we decide to do it that way?”

The value of an ADR lies in its structured format, which provides a universal language for technical decisions. It is typically comprised of several essential sections:

- Context: This section provides the background information that led to the decision. It is the narrative of the problem, including the organizational situation, business priorities, and any constraints or requirements that shape the choice.

- Considered Options: Here, the document lists the alternative solutions that were evaluated. Each option is presented with a detailed breakdown of its pros and cons.

- Decision: This is a clear, definitive statement of the chosen solution. It is accompanied by the core rationale and justification, explicitly referencing why a particular option was selected over the alternatives.

- Consequences: This section outlines the effects and outcomes of the decision. It describes what becomes easier, what becomes more difficult, and what necessary adjustments or follow-up actions are required for the team and the architecture.

While the value of ADRs is obvious, a quality, well thought-out ADR is time-consuming to produce and detracts from the creative, strategic work that architects do best.

This is where large language models (LLMs) and the field of prompt engineering offer a helping hand.

AI for architectural decisions

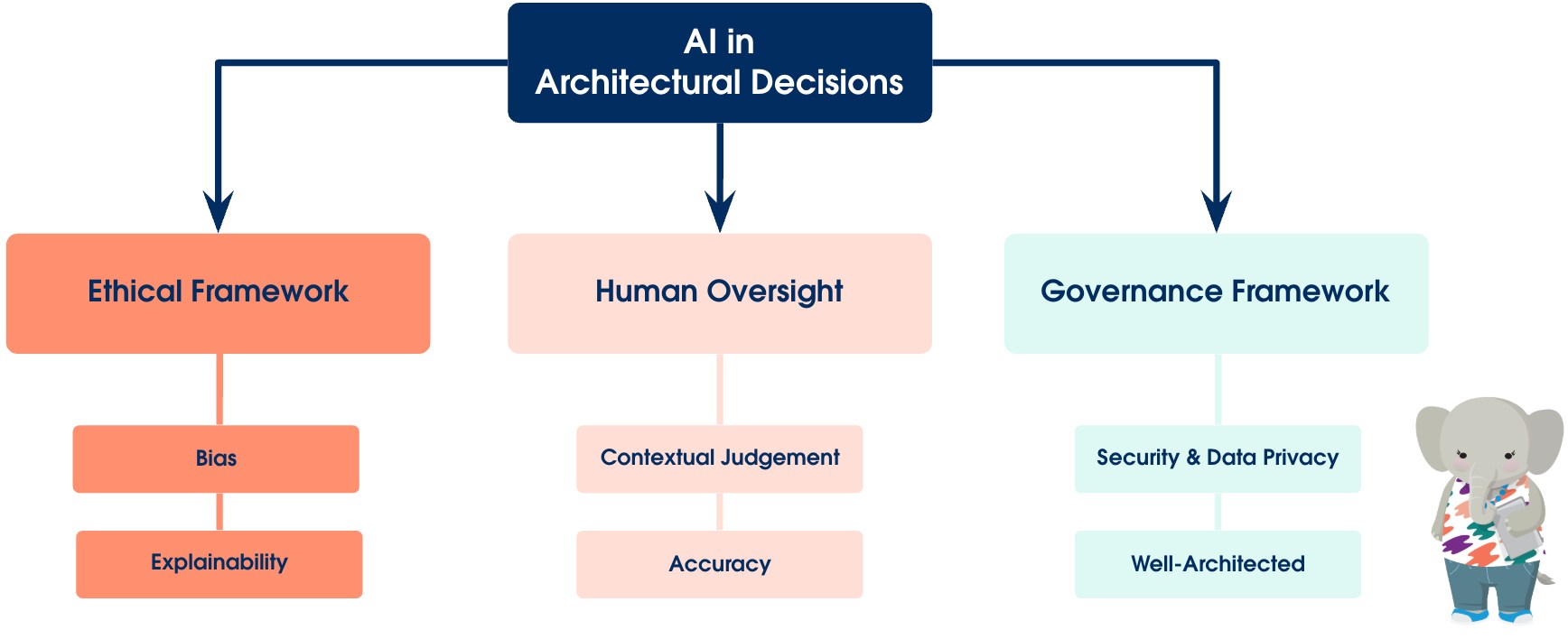

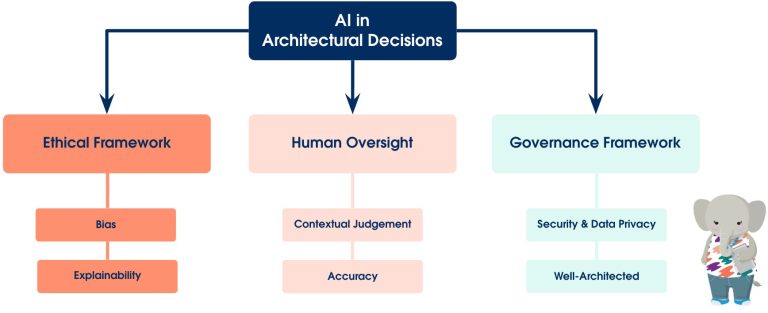

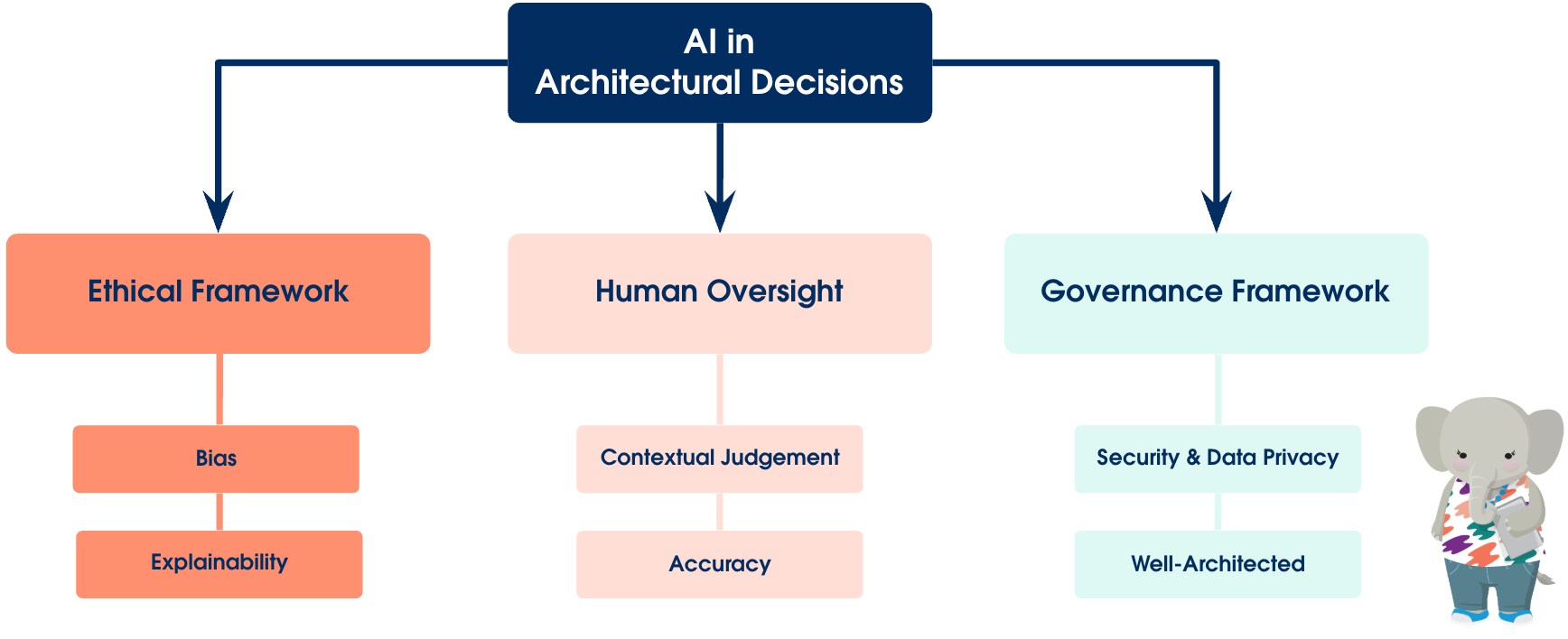

The effective use of AI in architectural design is not a one-prompt, simple hack, but a disciplined practice that requires a foundation of strategic principles.

When using AI for decision-making, an architect has to consider the negative consequences that can arise from relying on AI without proper oversight. LLMs can amplify societal biases through trained data, and the probabilistic nature of LLMs makes their results have a certain lack of explainability. Architects must be vigilant when reviewing outputs to ensure that they reflect a fair, well considered, and accurate outcome.

Human oversight

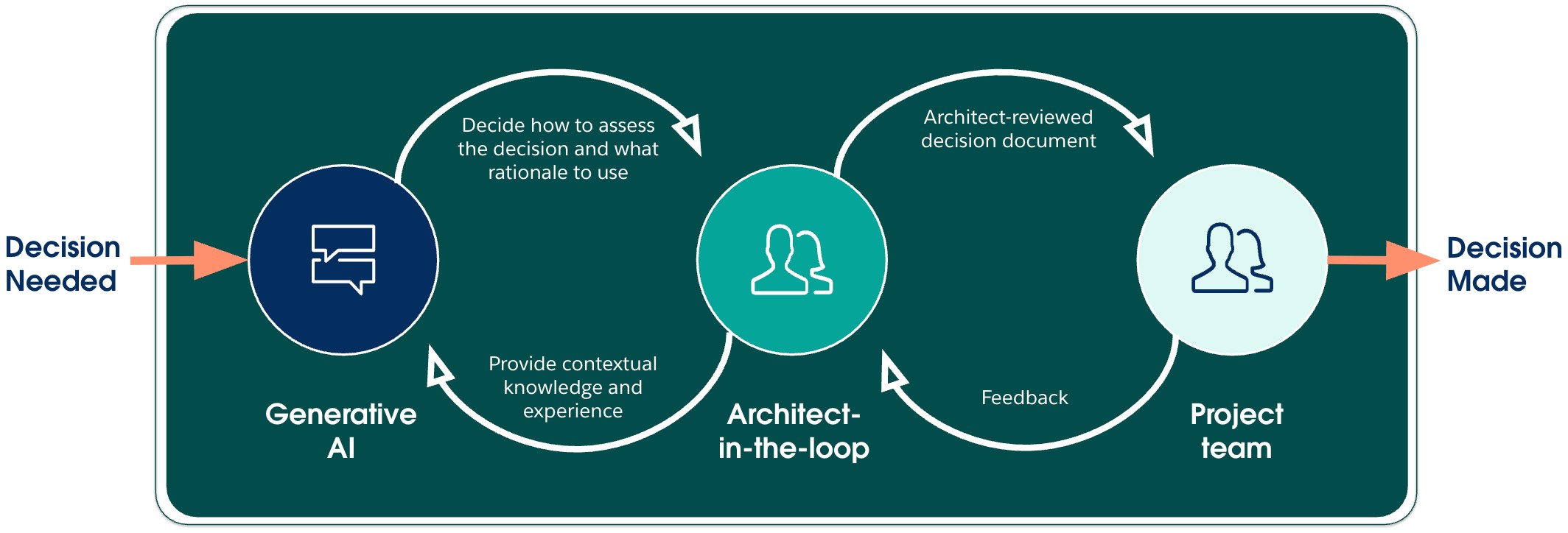

An AI-augmented world for decisions on projects needs a “human in the loop” (HITL), which is the ability for humans to intervene in automated systems to prevent disasters. In the context of generative AI when making architectural decisions, HITL is about giving the architect an opportunity to course correct AI-generated content.

I have also found that decisions I have made on projects have been more about stakeholder management than technical due diligence. It’s the contextual judgement — years of experience and showing empathy to concerned stakeholders — that drives a decision that is technically sound and widely supported. Ultimately the Salesforce Architect should be accountable for every key architectural decision made, regardless of AI’s involvement.

Governance framework

One implication of using AI to assist with architectural decisions is the risk of exposing sensitive, proprietary information. When an architect inputs a company’s confidential business requirements, data models, or solution designs into a public, general-purpose LLM, that data can be used to train the model, potentially leading to data leakage and intellectual property exposure. If you are using public LLMs like Claude, Gemini, and ChatGPT, make sure that you have reviewed the terms of service, ensure that they don’t use your inputs for training, and activate options to prevent your conversations from being used for training.

I also recommend including a formal disclosure in any outputs to build trust with project teams and ensure compliance with emerging ethical standards and potential regulations. Things to consider would be:

- The AI’s role In our case, to draft an ADR and summarize research of assessment options and rationale

- The tools used: Provide context and traceability of the model used

- An expectation on accuracy: Include clear statements that AI can make mistakes

- An accountability statement: State that the human architect is accountable for the final decision

To ensure that the decision-making process is not just about documenting generic pros and cons, but about evaluating choices against a structured set of criteria, I recommend using theSalesforce Well-Architected Framework. This helps cement any decisions you make as an architect with a set of well thought-out principles that prioritize security and compliance (Trusted), maintainability and user experience (Easy), and scalability and resilience (Adaptable). By anchoring the AI’s output in this framework, an architect can ensure that the final decision is grounded in a proven methodology for building healthy, long-term solutions on the Salesforce Platform.

Prompt engineering

Prompt engineering is the process of crafting prompts to guide generative AI models to produce specific outputs. Think of yourself as a conductor, directing the AI’s output with specific prompts to provide project context and experience. The grunt work of researching, drafting, summarizing, and formatting is delegated. It’s a process that can be repeated, at speed, to further refine your strategic thinking. Prompt engineering is therefore a natural companion when making decisions.

For a complex, multi-stage process, like a key design decision on a Salesforce project, a single, all-encompassing prompt is generally a less effective strategy. It’s a bit like asking a new team member to deliver a final solution after a single meeting; you’re just asking for well-meaning hallucinations. AI isn’t perfect. It can be unpredictable, inaccurate, and at times can make things up. In the context of your most important design decisions, that is not a good mix.

Instead, in order to keep a human in the loop, I advocate for a more architect-centric approach: prompt chaining. The AI is guided to produce a more project-specific, relevant, and accurate result by breaking the task into logical steps, with an architect diligently at the helm.

To look at this process in more detail, let’s take a look at a practical example.

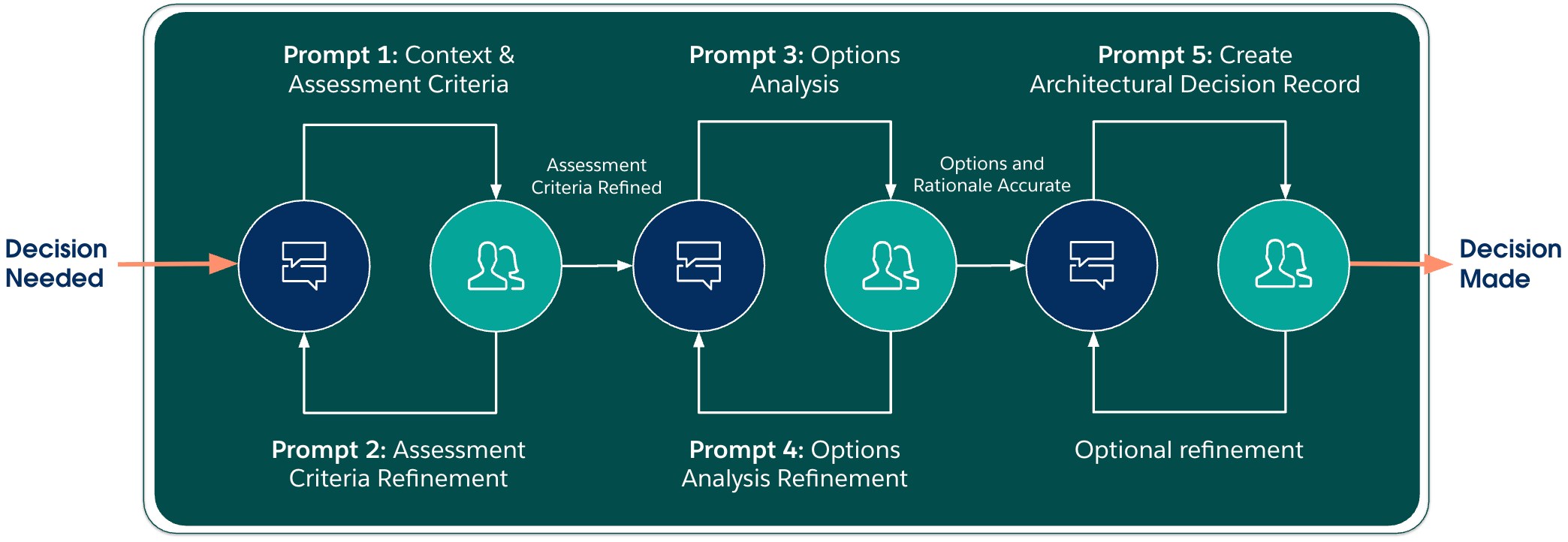

Practical walkthrough: Single-org vs. multi-org decisions

The following is a detailed, step-by-step walkthrough of a prompt strategy that I find helpful to generate an ADR for a common Salesforce design choice: whether to implement a single-org or multi-org architecture. We’ll walk through five sample prompts that demonstrate the concepts needed to produce a trusted result from generative AI using prompt chaining with an architect-in-the-loop.

Note: The sample outputs in the examples below were generated with Gemini 2.5. They are designed to show you the process and indicative sample outputs, not to be treated as an example of a final, validated outcome.

Prompt 1: Context & assessment criteria

This is the most crucial step: I tell the AI about the business problem and the high-level objectives. The goal here is not to ask for a solution, but to ask the AI to help me think about the problem more broadly by generating a list of objective assessment criteria.

My goal is to get the AI to analyze the business context and turn it into a list of key assessment criteria that are grounded in the Salesforce Well-Architected framework. I like to group them by the pillars: Trusted, Easy, and Adaptable.

The importance here is that the AI will likely suggest things I hadn’t even thought of. A good architect doesn’t think they know it all, and this is a chance to check for knowledge gaps. If you prefer to provide a pre-vetted list of criteria or your company’s established best practices, then you can modify the prompt accordingly.

This prompt revolves around the project context, and the more information you provide, the better. But it should include details about the organizational structure, specific business goals, known technical constraints, data governance policies, and any current pain points or challenges.

An example for CONTEXT in the prompt below could be:

The company is a growing global enterprise with approximately 15 departments all operating in Australia.

This covers, but is not limited to, a sales team, a contact center, a marketing team, a community affairs team, and customer billing.

Each department has unique processes but needs to share the same view of a business and its associated customers.

Some support items processed in the contact center need to be made private based on high value clients.

Some deals in the sales team need to be private unless people are added directly to support the sales activity

Case records need to be shared between at least five departments.

An existing case management system will be used in conjunction with Salesforce for at least three months, so an appropriate integration strategy where Case records mastered in Salesforce will be read only in the other case management system and vice versa until a full cutover is completed.

The leadership team has requested:

– Reporting across all departments

– A consistently applied data management strategy for key records, namely for Businesses and Contacts

– A deployment process that prioritizes speed

– A planned go-live in five months

– A focus on license costs, using only what is needed when it is needed

Individual departments have requested autonomy over their own business processes, but have acknowledged issues in the past with inconsistencies in how they document and share key records

The Salesforce team has 11 people: one project mgr, four developers, two administrators, two business analysts, a technical architect, and two solution architects. They all have prior experience running small sprints using an Agile methodology.

The output from this prompt is a list of key assessment criteria that can be used as the foundation for a decision grounded in the Salesforce Well-Architected framework.

| Role | Content |

| Architect | You’re a senior Salesforce Architect with deep expertise in enterprise-level architecture and the Salesforce Well-Architected framework. Your task is to draft a comprehensive and structured list of assessment criteria that a team of architects can use to evaluate a single-org vs. multi-org strategy.

<context> Output Requirements: Example Output: 2. Content: 3. Constraints: |

| Assistant | Trusted Data security and privacy: Evaluate how each org strategy (single vs. multi) would address the need for data privacy for high-value clients and specific sales deals. This includes assessing the complexity of managing private data access across multiple departments and the potential for data leakage. Data consistency and integrity: Assess how well each strategy supports a single, consistent data model for key records like Businesses and Contacts. Consider the challenges of synchronizing data and enforcing a unified data management strategy across a multi-org environment versus the governance required in a single-org. System and data governance: Determine the level of governance required to maintain a secure and consistent environment. The criteria should address how a single org can manage conflicting requirements and how a multi-org strategy can enforce consistent standards and data policies across disparate systems. Compliance and reporting: Evaluate the ease of implementing enterprise-wide reporting and ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements. A single org simplifies reporting across all departments, while a multi-org strategy would require a robust integration or reporting layer, adding complexity and potential for reporting inconsistencies. Easy Adaptable |

Prompt 2: Assessment criteria refinement

Now for the “human-in-the-loop” part. I review the AI’s output and, more importantly, inject my own experience and knowledge. The AI is a great sounding board, but it doesn’t have the context of my project’s specific nuances. For example, I might add a criterion about the difficulty of “splitting or merging” an org later on, or I might correct an assumption the AI made (like the need to omit anything to do with data sovereignty in the criteria).

This step is where I add criteria specific to the project and include items that address key stakeholder concerns. The output from this prompt is an updated list of key assessment criteria — one that has had a human in the loop — that can be used as the foundation for the decision. I repeat this process and continue research, if needed, until I believe that the criteria accurately reflect the state of play on my projects.

An example for ITEMS in the prompt below could be:

New assessment criteria:

Splitting or merging: What are the implications of changing the decision at a later date — either splitting from a single org or merging an initial multi-org strategy. Note that initially the greenfield implementation will be small and only three departments have functionality included in the first two releases.

Update assessment criteria:

Data security and privacy: Also add the fact that regulatory requirements are not important from a data sovereignty POV since any future growth is limited to Australia only.

In this example a new criterion was added in the adaptable section to add a concern from a stakeholder.

| Role | Content |

| Architect | Your task is to review and update an existing set of assessment criteria based on new information.

<items> Output requirements: Example output: 2. Content: 3. Constraints: |

| Assistant | As a senior Salesforce Architect, here is a comprehensive list of assessment criteria for comparing a single vs. multi-org strategy. These criteria are categorized by the Salesforce Well-Architected framework pillars to guide the architect team’s evaluation.

Trusted Data security and privacy requirements: Evaluate the complexity of implementing data privacy rules, such as those for confidential support items or private sales deals. A single org requires a highly granular and complex sharing model, while a multi-org strategy could use separate orgs to enforce security by isolation. Business continuity and disaster recovery: Assess the risk and impact of a system outage. In a single org, an outage affects all departments, whereas a multi-org strategy can isolate issues, allowing unaffected departments to continue operations. Data governance and compliance: Consider the effort required to enforce a consistent data management strategy for key records like Businesses and Contacts. A single org simplifies this by using standard objects and validation rules, but a multi-org setup requires a dedicated master data management (MDM) solution to synchronize data and ensure consistency across orgs. Easy Deployment and release management complexity: Assess the time and effort required for deployments. A single org, with its single codebase, simplifies continuous integration and delivery (CI/CD) pipelines. A multi-org strategy necessitates managing separate pipelines for each org, which can be more complex and slower, directly impacting the leadership team’s request for a fast deployment process. Operational and administrative overhead: Evaluate the long-term effort to administer the Salesforce environment. A single org simplifies user, profile, and permission set management. A multi-org approach requires the team to manage multiple sets of configurations, users, and licenses, increasing administrative burden. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): Compare the costs associated with both strategies. A multi-org setup may incur higher overall licensing costs due to separate license pools for each org, which might conflict with the goal of using licenses only as needed. A single org can leverage license sharing and a single license pool to optimize costs. Adaptable Splitting or merging: Assess the implications of changing the org strategy later. While an initial small greenfield implementation makes a single org seem easier, splitting it later can be a significant and complex undertaking. Conversely, merging multiple orgs is a large-scale data and technical migration project. Scalability and performance: Assess the ability of the system to handle future growth in users and data. A single org’s performance can degrade as more departments add custom objects and automation, leading to governor limit issues. A multi-org strategy provides horizontal scaling by isolating department-specific functionality and data in different orgs. Departmental autonomy and flexibility: Evaluate how each strategy supports the departments’ requests for autonomy over their unique business processes. A multi-org strategy grants each department full control over its org, allowing for tailored configurations and rapid changes without affecting others. A single org requires a more centralized governance model, which can slow down innovation for individual departments. Integration complexity: Consider the effort to integrate with internal and external systems. A single org has a consolidated data model, making integrations straightforward. In a multi-org setup, creating a unified view of the customer requires complex integration between the orgs themselves, adding significant architectural overhead and potential data latency. |

Prompt 3: Options analysis

This is where the AI really earns its keep. It takes the refined assessment criteria and generates a comprehensive, side-by-side comparison of the two options (single-org vs. multi-org). I use a simple risk rating system — Low, Medium, and High — to quantify the trade-offs.

I don’t have to manually create a giant table and fill in the details. The AI does the heavy lifting, giving me a starting point for my analysis. It’s like having an architect assistant generating draft documents for me to review.

An example for RATING in the prompt below could be:

A risk rating must be split by these key values:

*Low: The option presents a low risk of impacting current or future requirements, performance, or scale

*Medium: The option has some risk unless proper governance is in place

*High: The option has a high risk of impacting current or future requirements, performance, or scale

| Role | Content |

| Architect | Explain the key architectural considerations and trade-offs of each option (single-org vs. multi-org) vs the assessment criteria. Use the rating system below.

<rating> Output requirements: Example output: 2. Content: 3. Constraints: |

| Assistant | Trusted | ||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| Data Governance & Security Model | Risk: Medium. All data resides in a single instance, requiring a robust and complex security model (role hierarchy, permission sets, sharing rules, etc.) to enforce privacy for sensitive data. Data governance is centralized but requires significant effort to manage department-specific processes without creating inconsistencies. | Risk: Low. Data is physically isolated, simplifying security and privacy requirements. Each org can have a simpler security model tailored to its specific needs, inherently protecting private data (e.g., private support cases and sales deals) from other departments. | |

| Compliance & Data Privacy | Risk: Low. Centralized data makes it easier to track and audit data for regulatory compliance. It provides a single point of truth for reporting and data management, simplifying compliance overhead. | Risk: Medium. Data isolation can be an advantage for certain regulatory requirements (like data residency). However, managing compliance across multiple, separate orgs can create administrative overhead and requires a clear governance strategy to avoid inconsistencies. | |

| User Access & Permissions | Risk: Medium. Managing a large number of users with varying levels of access to shared objects is complex. The security model can become intricate and difficult to maintain, increasing the risk of over-provisioning access or errors. | Risk: Low. User access is contained within each org. Permissions are simpler to define as they’re specific to the departmental context, reducing complexity and the risk of accidental data exposure across departments. | |

| Reliability & Availability | Risk: High. A single point of failure. Any major outage or performance issue with the org impacts all 15 departments simultaneously. A single org also has hard governor limits that could be hit by one department’s usage, affecting everyone. | Risk: Low. Issues are isolated to a single org. If one department experiences a problem, it won’t impact the availability or performance of other departments, ensuring business continuity across the organization. | |

| Easy | |||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| User Experience (UX) & Autonomy | Risk: High. Providing autonomy is difficult. A single org requires a high degree of standardization, and department-specific changes can be blocked or delayed if they conflict with other teams’ needs. This can lead to a generic UX that doesn’t fully meet individual department needs. | Risk: Low. Each department has full autonomy to customize their org and user experience to match their unique processes and workflows. This allows them to iterate and innovate faster without impacting others. | |

| System Integrations | Risk: Low. All data is in one place, so integrations are simpler and more direct. There’s a single endpoint for external systems, reducing the complexity of middleware and integration management. | Risk: High. Integrating data that needs to be shared (like Businesses and Contacts) across multiple orgs is complex. It requires a robust integration strategy and middleware to maintain data consistency and a shared view, increasing development time and cost. | |

| Deployment & DevOps | Risk: High. A single deployment pipeline for all departments leads to a “bottleneck.” Deploying changes requires extensive regression testing to ensure no other department is negatively impacted, making the planned five-month go-live difficult to achieve. | Risk: Low. Departments can manage their own deployment processes. This allows for faster and more frequent releases within each team, supporting the requested speed. However, coordinating cross-org changes requires a robust release management strategy. | |

| Maintenance & Administration | Risk: Medium. Streamlined administration with a single instance to manage. However, the complexity of the shared codebase, intricate sharing rules, and a large number of users requires a highly skilled and dedicated team to manage. | Risk: High. Requires multiple Salesforce administrators, one for each org, or a team with expertise across all orgs. Duplicated administrative tasks, such as user provisioning and managing settings, increase overhead and cost. | |

| Adaptable | |||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| Splitting or Merging | Risk: High. While initially simple for a small greenfield project, splitting a single org is a massive and costly undertaking. It’s a complex data and metadata migration project with significant risk and business disruption. It’s not a decision to be taken lightly. | Risk: Low. Merging multiple orgs is also a large project, but it is often less complex than splitting a highly customized, monolithic single org. It’s a more manageable migration from a technical perspective. | |

| Scalability & Performance | Risk: High. All departments share the same resources and governor limits. High data volume, complex customizations, or a high number of API calls from one department can cause performance degradation for everyone and can lead to hitting platform limits. | Risk: Low. Workload is distributed, reducing the risk of hitting governor limits. Each org has its own set of limits, allowing individual departments to scale without impacting others. | |

| Innovation & Autonomy | Risk: High. Innovation is slower and more restricted. Any new feature or change must be vetted by a central governance body to ensure it doesn’t conflict with other departments, stifling departmental autonomy and speed. | Risk: Low. Departments can innovate and implement their own unique business processes quickly and independently. This model supports the requested departmental autonomy without the need for central approval for every change. | |

| Reporting & Analytics | Risk: Low. Consolidated reporting is native and straightforward since all data is in one place. It is easy to create a “360-degree view” of the customer across all departments, which is a key leadership requirement. | Risk: High. Consolidated reporting is challenging and requires a separate solution (like Salesforce Data Cloud or an external data warehouse) to pull data from multiple orgs. This adds significant cost and complexity to meet a key leadership requirement. | |

| Cost of Ownership | Risk: Low. Generally more cost-effective due to shared licenses, sandboxes, and administrative resources. A single org provides better economies of scale for a growing company. | Risk: High. Higher license costs for each org and potentially for additional integration tools. Duplicated administrative and development efforts across orgs increase the total cost of ownership. | |

| Team Skills & Bandwidth | Risk: Medium. Requires a highly skilled team capable of managing a complex, enterprise-level system. Strong governance and technical architecture skills are critical to prevent technical debt and maintain performance. The current team of nine agile developers may be stretched thin. | Risk: Low. A team of nine can be split to focus on specific departmental orgs, allowing them to become experts in a particular area. This model can better leverage the team’s agile methodology and focus on small, independent sprints. |

Prompt 4: Options analysis refinement

This is where I get to add the “architectural nuance.” I take the AI’s table and correct it. I challenge its assumptions and inject the subtle, on-the-ground knowledge that only a human on the project can have. For instance, while the AI might suggest merging orgs is “easy,” I know from experience that if each department has been customizing their data model, a future merge would be a total nightmare.

This step is critical. It allows me to create a more human, nuanced view of the considerations at play — one that can be reviewed by all stakeholders. It’s the final check to ensure that the AI’s analysis is not just accurate, but also relevant and tailored to the project. I, again, repeat this process for as long as needed to make sure the rationale against each criteria accurately reflects the uniqueness of the project.

An example for AMENDMENTS in the prompt below could be:

Splitting or merging: This assessment should be updated to reflect the fact that since each department has autonomy, it is likely that the data model diverges quickly for shared objects like Contact. This makes merging orgs a high risk and more difficult than splitting — which is a low risk — in the short to medium term.

Scalability & performance:

While a single org strategy does share platform limits, the number of licenses being purchased lowers this risk to a medium from high.

Collaboration & autonomy:

While a central governance body may slow change management, the benefit in having a consistent view of Business and Contacts outweighs any negative. A single-org strategy then becomes a medium risk, with the multi-org a high risk since it leads to multiple conflicting data models that later have to be reconciled for reporting

Deployment & release management:

The risk to a single-org strategy is low. There is one set of environments, easier to coordinate sandboxes and data loads. For a multi-org approach, the ideal would be to have separate teams manage each environment, but the small team size here would make this difficult in the short to medium term as rated as medium risk.

This outputs a more human, nuanced view of the considerations at play.

| Role | Content |

| Architect | Update the key architectural considerations and trade-offs for each option (single-org vs. multi-org) vs the assessment criteria based on the amendments below.

<amendments> Output requirements: Example output: 2. Content: 3. Constraints: |

| Assistant | Trusted | ||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| Data Governance & Security Model | Risk: Medium. All data resides in a single instance, requiring a robust and complex security model (role hierarchy, permission sets, sharing rules, etc.) to enforce privacy for sensitive data. Data governance is centralized but requires significant effort to manage department-specific processes without creating inconsistencies. | Risk: Low. Data is physically isolated, simplifying security and privacy requirements. Each org can have a simpler security model tailored to its specific needs, inherently protecting private data (e.g., private support cases and sales deals) from other departments. | |

| Compliance & Data Privacy | Risk: Low. Centralized data makes it easier to track and audit data for regulatory compliance. It provides a single point of truth for reporting and data management, simplifying compliance overhead. | Risk: Medium. Data isolation can be an advantage for certain regulatory requirements (like data residency). However, managing compliance across multiple, separate orgs can create administrative overhead and requires a clear governance strategy to avoid inconsistencies. | |

| User Access & Permissions | Risk: Medium. Managing a large number of users with varying levels of access to shared objects is complex. The security model can become intricate and difficult to maintain, increasing the risk of over-provisioning access or errors. | Risk: Low. User access is contained within each org. Permissions are simpler to define as they’re specific to the departmental context, reducing complexity and the risk of accidental data exposure across departments. | |

| Reliability & Availability | Risk: High. A single point of failure. Any major outage or performance issue with the org impacts all 15 departments simultaneously. A single org also has hard governor limits that could be hit by one department’s usage, affecting everyone. | Risk: Low. Issues are isolated to a single org. If one department experiences a problem, it won’t impact the availability or performance of other departments, ensuring business continuity across the organization. | |

| Easy | |||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| User Experience (UX) & Autonomy | Risk: High. Providing autonomy is difficult. A single org requires a high degree of standardization, and department-specific changes can be blocked or delayed if they conflict with other teams’ needs. This can lead to a generic UX that doesn’t fully meet individual department needs. | Risk: Low. Each department has full autonomy to customize their org and user experience to match their unique processes and workflows. This allows them to iterate and innovate faster without impacting others. | |

| System Integrations | Risk: Low. All data is in one place, so integrations are simpler and more direct. There’s a single endpoint for external systems, reducing the complexity of middleware and integration management. | Risk: High. Integrating data that needs to be shared (like Businesses and Contacts) across multiple orgs is complex. It requires a robust integration strategy and middleware to maintain data consistency and a shared view, increasing development time and cost. | |

| Deployment & DevOps | Risk: High. A single deployment pipeline for all departments leads to a “bottleneck.” Deploying changes requires extensive regression testing to ensure no other department is negatively impacted, making the planned five-month go-live difficult to achieve. | Risk: Low. Departments can manage their own deployment processes. This allows for faster and more frequent releases within each team, supporting the requested speed. However, coordinating cross-org changes requires a robust release management strategy. | |

| Maintenance & Administration | Risk: Medium. Streamlined administration with a single instance to manage. However, the complexity of the shared codebase, intricate sharing rules, and a large number of users requires a highly skilled and dedicated team to manage. | Risk: High. Requires multiple Salesforce administrators, one for each org, or a team with expertise across all orgs. Duplicated administrative tasks, such as user provisioning and managing settings, increase overhead and cost. | |

| Adaptable | |||

| Assessment Criteria | Single-Org Considerations | Multi-Org Considerations | |

| Splitting or Merging | Risk: Low. While it is a massive undertaking, splitting an org that has maintained a consistent data model for shared objects is relatively more straightforward. This option provides flexibility for future business decisions. | Risk: High. Since each department can autonomously customize their data model, merging these divergent models later to achieve a unified view is a massive and highly complex data migration and reconciliation project. It poses a significant risk to the business. | |

| Scalability & Performance | Risk: Medium. While all departments share the same resources and governor limits, the limited number of initial licenses being purchased lowers the immediate risk of hitting those limits. The risk increases as the organization grows. | Risk: Low. Workload is distributed, reducing the risk of hitting governor limits. Each org has its own set of limits, allowing individual departments to scale without impacting others. | |

| Innovation & Autonomy | Risk: Medium. While a central governance body may slow change management, it ensures a consistent view of Business and Contacts. This benefit outweighs the negative impact of slower innovation, leading to a more reliable platform and reporting foundation. | Risk: High. Uncontrolled departmental autonomy leads to conflicting data models for core objects like Business and Contacts. This creates significant technical debt and makes cross-departmental reporting and analysis difficult to impossible without major, costly reconciliation projects. | |

| Reporting & Analytics | Risk: Low. Consolidated reporting is native and straightforward since all data is in one place. It is easy to create a “360-degree view” of the customer across all departments, which is a key leadership requirement. | Risk: High. Consolidated reporting is challenging and requires a separate solution (like Salesforce Data Cloud or an external data warehouse) to pull data from multiple orgs. This adds significant cost and complexity to meet a key leadership requirement. | |

| Cost of Ownership | Risk: Low. Generally more cost-effective due to shared licenses, sandboxes, and administrative resources. A single org provides better economies of scale for a growing company. | Risk: High. Higher license costs for each org and potentially for additional integration tools. Duplicated administrative and development efforts across orgs increase the total cost of ownership. | |

| Team Skills & Bandwidth | Risk: Medium. Requires a highly skilled team capable of managing a complex, enterprise-level system. Strong governance and technical architecture skills are critical to prevent technical debt and maintain performance. The current team of nine agile developers may be stretched thin. | Risk: Low. A team of nine can be split to focus on specific departmental orgs, allowing them to become experts in a particular area. This model can better leverage the team’s agile methodology and focus on small, independent sprints. |

Prompt 5: Architectural decision record creation

This is the final step. I’ve done my due diligence, reviewed the options, and made a judgement call. Now, I tell the AI my final decision and ask it to draft the ADR document. It takes all the previous information — the context, the criteria, the risks, and my final decision — and formats it into the professional, concise document I need.

I’m not a writer; I’m an architect. The AI does the heavy lifting of combining all that information into a coherent document, leaving me to focus on the content and the strategic implications.

An example for DECISION in the prompt below could be:

Based on current requirements, the recommendation is to conduct development activities for this project in one org. Single org agility is the biggest concern moving forward, and it is recommended to review this decision in six months.

| Role | Content |

| Architect | Draft an architectural decision record (ADR) using the decision recorded.

<decision> Output requirements: Metadata: AI usage disclosure: This ADR was drafted with assistance from Gemini 2.5. Each assessment criteria and rationale was reviewed by each decision-maker listed above. The final recommended decision was made by carefully reviewing the rationale for accuracy. Core ADR sections: Considered options: Detail two distinct architectural approaches: **Single-Org** and **Multi-Org**. Decision: Consequences: Appendix: 2. Constraints: |

| Assistant | Architectural Decision Record: Salesforce Org Strategy

ADR #: 001 AI Usage Disclosure: This ADR was drafted with assistance from Gemini 2.5. The final review and decision was made by Max Astro. 1. Context 2. Considered options Option 1: Single-org strategy Pros: Cons: Option 2: Multi-org strategy Pros: Cons: 3. Decision Rationale: 4. Consequences What becomes more difficult |

Chaining prompts together, with checkpoints for review, produces a reusable workflow for architectural decisions that prevents architects from starting with a blank page. I personally like this approach as it can be applied to any key design decision with the initial prompt setting context and the assessment criteria flexibly refined based on the objective.

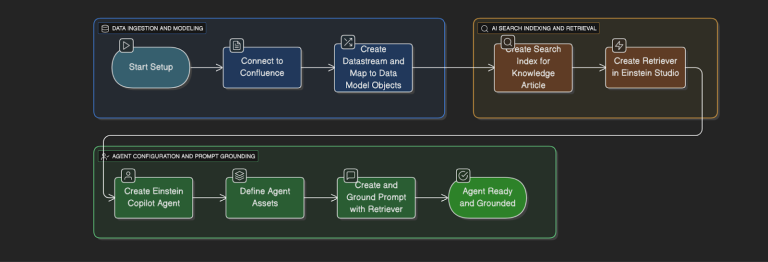

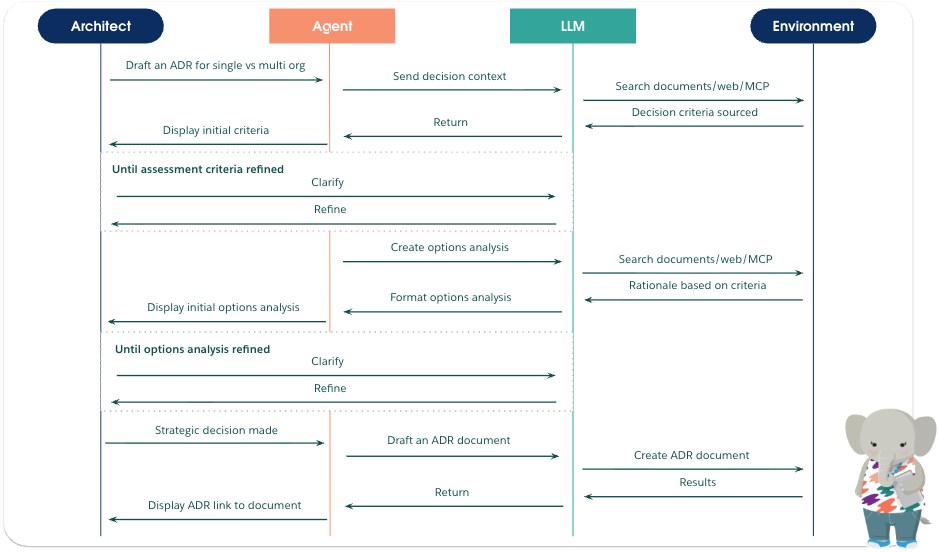

Automating the decision process with AI agents

While a manual, chat-driven, human-in-the-loop workflow is a great time saver, the future of this type of process lies in autonomous agents. These agents move beyond simple, prompt-response cycles to proactively manage entire workflows, reducing the need for constant manual interaction and a “back and forth”.

A more advanced agentic process would be asynchronous and event-driven, leveraging Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Model Context Protocol (MCP) to enhance accuracy and relevance. RAG allows an agent to access internal, trusted knowledge bases to retrieve assessment criteria based on a company’s best practices. MCP is the standardized protocol that allows an AI model to access the live metadata of a Salesforce org, improving the architect’s ability to understand a brownfield implementation when making decisions. The architect’s role shifts from constantly prompting the agent to overseeing a multi-stage process that the agent manages autonomously.

Creating agents like this that support project teams with high quality documentation would be a great addition to Salesforce. Agentforce, Flow, and Prompt Builder are well-positioned to provide a good starting point using the Einstein Trust Layer. But that is perhaps a detailed post for another day.

Conclusion

When documenting key design decisions, it is important to always have an answer to “Why? Why did they build it this way?”While AI can greatly accelerate documentation, it is critical to implement a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) paradigm to ensure accuracy and relevancy. The core limitation of large language models (LLMs) is that they operate on “pattern recognition – not comprehension.” They can generate amazing content, but they lack the professional judgement, business context, and empathy required to make a truly sound architectural decision.

The effective use of AI in architectural design decisions is not a one-prompt, simple hack, but a disciplined practice that requires a foundation of strategic principles.

- Adopt a disciplined approach to key decisions: Whether you use an ADR or not, use a consistent format to help communicate decisions across your projects.

- Lead with the Salesforce Well-Architected framework: Use the Trusted, Easy, and Adaptable pillars as the standard for evaluating every decision.

- Master prompt engineering: Go beyond simple queries by embracing persona-based, contextual, and chained prompts to guide the AI’s reasoning. Refine and fix accuracy issues and inject your Salesforce experience into the process.

- Integrate Human-in-the-Loop: An architect’s expertise is still the only way to consistently validate AI-generated outputs. The architect is ultimately responsible for ensuring the final output is sound.

- Automate with agents: When needed, move beyond simple, prompt-response cycles to proactively manage entire workflows, reducing the need for constant manual interaction and a “back and forth.”

Ultimately, generative AI can elevate an architect’s role. The AI can handle the repetitive, boring work of drafting and formatting, but your expertise is what drives quality decisions. This frees you to focus on making the strategic calls that build a Well-Architected solution.

Resources

- Trailhead: Salesforce Well-Architected Framework

- Trailhead: Prompt Fundamentals

- Trailhead: Prompt Engineering Techniques

- Documentation: ADR GitHub organization